Versage is an exploration of low-end globalization and global inequality; contemporary Nigerian fashion and the people behind it; the notion of cheapness; the complexity of the concept of "Made in China"; the creolization of taste; and when mimicry becomes its own aesthetic. See how Versage trade is working on the streets of Lagos

In Lagos, golden hour is also traffic hour is also business hour on streets too slim for the cars they contain. A young man wears a t-shirt dotted with a Medusa head in gold appliqué and bold face type that reads VERSAGE. He carries a plasticky tarpaulin bag of plantain chips, scanning windows of cars as he snakes through the hard rumbling bodies, an outer world of encasements. The window of a black Mercedes SUV cracks open and a thick, soft, bejeweled hand waves. Lips hiss a kiss. The plantain vendor sprints, balancing his load. Through the slit in the window, the rich hand selects from a bouquet of flavors. The rich hand is clutching a 500 Naira note. The poor hand bumbles through a wad of sweaty bills to unfurl two wrinkled 200s and passes them to his customer. He can see the soft silk shirt and feel the blast of the AC through the crack between their worlds. The traffic breaks and the car accelerates. The rich hand drops the money in the wind. It flutters toward the gutter. The poor man chases it, between the cars, stoops to retrieve it, then moves to the side. He pulls out a handkerchief and wipes his face, drooping exhaustion and dripping sweat under a bedazzled cap that spells, in sequins, “BOSS”.

Street fashion in Lagos is aspirational. Contemporary knock off designer street wear—what I call Versage after the common writing of the Versace knock offs—is at once what the wearer wishes to be, and what the wearer actually is. The aesthetic is glamorous and loud, it screams of money, for money. But it is also cheap. There are knock off designer goods all over the world, but the Nigerian expression of it is distinct. Vendors and traders observe what is hot, what is selling, on the streets of Lagos and then tweak new designs to feed the voracious, ever evolving market. “We are inquisitive when it comes to fashion, curious. And we are also creative. We steal, we change, we make some changes, and add things to it,” Chibuzo, a shoe designer and businessman, explained. Mimicry of designer looks creolizes with Nigerian taste to become a new, distinct aesthetic. No one believes that they are buying Italian Versace when they buy Versage, they are rather shopping for something made specifically for the low-class Nigerian consumer: fashionable, fine and affordable.

Versage is an aesthetic that exists because of the omnipresence of interactions like that between the plantain vendor and his customer. Lagos is a land of extremes. Extravagance and deprivation slip past each other. The poor cannot help but stare at the wealthy, while the rich do their best to avert their gaze. Invisibilization is one form of oppression. Mimicry is a stilted covetousness.

“People like to dress well, especially Nigerians they like to dress well,” explained Daniel, a Nigerian fashion designer and businessman. “No matter how much you have in your pocket, you may not have anything, but when you dress neat, then you derive joy from keeping yourself neat, wearing clothes. So in Nigeria, in Africa…anyone who sells clothes must surely take care of himself and family.”

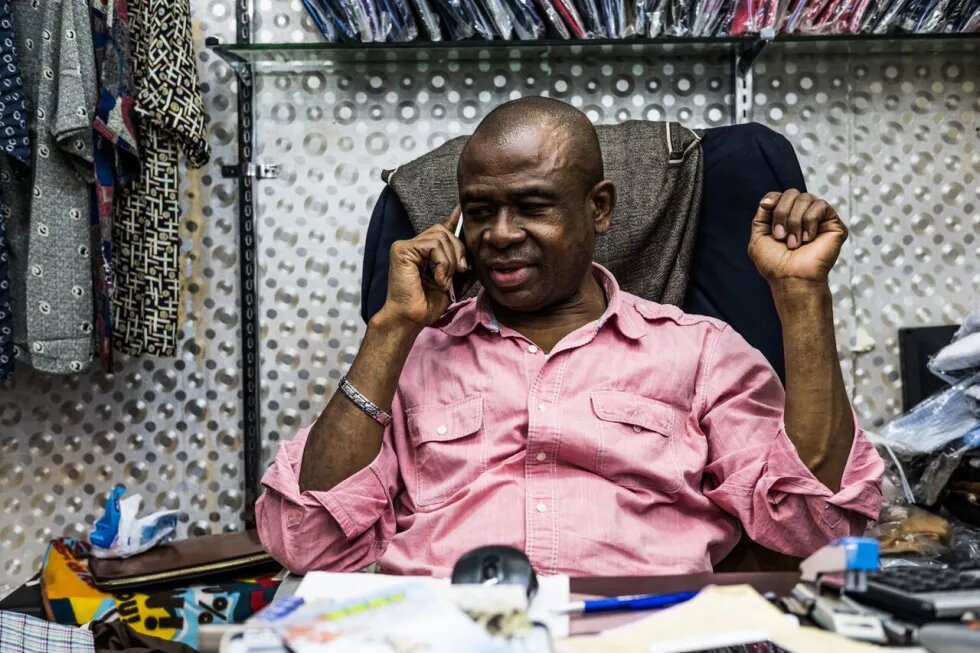

Versage is an aesthetic that exists also because of the ingenuity, independence, and creativity of Nigerian entrepreneurs. Behind Versage are mostly men, mostly Igbo, who travel back and forth to southern China, curating and designing clothing for the ravenous fashion market that starts in Lagos and extends along spidery pathways across Nigeria and West Africa. There are myriad fashion markets in Nigeria: used clothing from the UK shipped through Benin; overstocks from Turkey, Vietnam and Thailand; lace from Austria; adire from Ibadan; the remnants of a local textile manufacturing industry in Kaduna that produces “fancy” and grey cloth; factories in Aba that produce knock-off knock-offs: Nigerian made shoes printed with “Made in China” or “Made in Italy”. All these clothes serve a purpose, act as an identifier, a social definition. But this story is about Versage and the people behind it. It is a transnational story of what anthropologist Gordon Mathews calls “low-end globalization”. In his 2011 book Ghetto at the Center of the World, he writes: “Low-end globalization is very different from what most readers may associate with the term globalization—it is not the activities of Coca-Cola, Nokia, Sony, McDonald’s and other huge corporations, with their high rise offices, batteries of lawyers, and vast advertising budgets. Instead, it is traders carrying their goods by suitcase, container or truck across continents and borders with minimal interference from legalities and copyrights, a world run by cash…This is the dominant form of globalization experienced in much of the developing world today.” Much of the Versage business is highly individual and small scale. Sixty-five percent of traders work alone, with no paid staff, and less than 10% have more than two employees, according to the Lagos Trader Survey (LTS), a representative panel study of traders in Lagos' plazas. Almost three quarters of traders are male, and over half are importers. The project by Shelby Grossman and Meredith Startz, researchers at the University of Memphis and Princeton, covers traders throughout Lagos. The Versage designers and distributors fit into this broader picture. From conception through the creation, transport, importation and sale of street wear, individual Nigerians are running the business.

The Versage trade crosses back and forth from Lagos to China and between the formal and informal realms. Around two thirds of Nigeria’s economy is “informal” but this is a charged word that lacks an agreed upon definition. Informality is what happens when the formal has no space for what the market or society demands. Like when the government fails to place a crosswalk at an intersection that pedestrians must traverse, so they cross anyway, pounding a pathway through the central median. So, traders circumvent visa restrictions and import bans to bring goods to Nigerian consumers. When the formal structures are long absent, the informal solidifies. In Lagos the informal market is methodical, if unwritten. It is constantly evolving, but there are rules and hierarchies to the game. Government is interwoven with alternative power structures: market associations and area boys. Government agents enforce rules sporadically, and not necessarily to the letter.

“In the Lagos context, when you have traders who are called informal, they’re informal in only the most narrow sense of the definition, which is that they are not registered with the Lagos State Corporate Affairs Commission. But they pay local government taxes, often their shops are on local government land, so they're literally paying rent to the local government…It’s not like black market in the sense that the government doesn't know what's going on, the government very much knows what's going on,” explained Grossman, the LTS researcher.

Mandilas, a subsection of Balogun market on Lagos Island is the locus of Versage. It is both the central distribution point and also, with its crowd of fashion consumers and retailers, it is the inspiration hub for new designs. Bright t-shirts, studded jeans, and sparkly shoes cram streets and alleyways, shrinking roads to a thin pedestrian path. Goods are laid out on mats; dangled from constructed stands like an umbrella; suspended from makeshift extensions to the buildings; or stacked in several-story plazas. Balogun is overwhelming because so many people work there, each running a small operation, that together create the bustling chaos you feel on the street. Unlike the corporate world of big box clothing retailers, Nigeria’s fashion importation and distribution model is diffuse; a pointillist constellation of businesses comprise the market. The risks and the successes, the relentless boom and bust cycles of poverty and investment all fall on the shoulders of the individuals. It is difficult to estimate the number of these small-scale shops. But Grossman and Startz have tallied over a hundred market associations in Lagos island, each of which have dozens of members. Another way to estimate the scale is through BuyChat and BalogunMarket.ng, internet companies that put the traders from Balogun market online. The founder, Olayinka Oluwakuse has registered 7,000 vendors in Balogun, 1,000 of which are in fashion, the largest single category. He said that the vast majority of fashion transactions in the country come through Balogun market. “The biggest importers are in that market, they cater to the bottom of the pyramid, the wholesale. Most of the clothing in town comes from that market,” he said. He estimates that 60 percent of customers in Balogun are traders themselves. They buy in bulk then resell the clothes across the country, in small shops, from the trunks of their cars, or online on instagram and whatsapp.

Along the edges of the streets, vendors fold and refold clothing, and watch the world pass by. They observe trends shifting, and new patterns gaining popularity. Then they communicate that with their brothers in China. An eighteen hour flight away, Nigerians in China are placed at the source, selecting and creating the fashion that will soon strut through the streets of Lagos. Guangzhou is the largest city in the Pearl River Delta in Southern China. The area has been dubbed the factory floor of the world, and Guangzhou is the textile node. China produces and exports the most garments of anywhere in the world, three times as much as India, the second largest producer. Shoppers balance massive bags of clothes over their shoulders, a spare pair of jeans dangling out. Many Nigerians weave through the streets. They mostly travel on tourist visas and many overstay. They live in constant states of “precarity, liminality and unbelonging” according to Roberto Castillo, a lecturer at the African Studies Program of the University of Hong Kong who has extensively researched Africans in China. At least 16,000 Africans live in Guangzhou, though it is nearly impossible to count given the transience of the population. They work independently, often learning the ropes from another freelance trader during their initial months in China.

China came to dominate the textile trade because of its cheap labor costs, state support of the sector, and also because of lax regulations. In China you get what you pay for, and can special order clothes to be cheaper. This is an important factor for the Nigerian buyers who are catering to consumers that are among the poorest in the world. “If you make quality things and send to Africa not everybody will buy, but if you have cheap items, people will rush to buy it,” Daniel explained. Africa, he said, needs “substandard.”

The factories in China are stacked in nondescript lofts or tucked along alley ways. Job boards on surrounding street corners are speckled like confetti with the remnants of flyers. Many of the factories are small family businesses. One factory I visited looked like a garage. A handful of workers attached sleeves to t-shirts and tags to polos at sewing machines lined up in rows. In between, giant bags were stacked with Versage shirts for Nigeria, and wax print inspired bikinis bound for South Africa. The interactions between Nigerian traders and designers and the factory owners is also individual and personal, which allows for the ducking beneath regulations. If it is good for business, and mutually beneficial, bans on knock-offs can be willfully forgotten.

Kingsly goes to the fabric market every morning, walking through the aisles, fingering the rolls of fabric spilling out from the shops. He buys loud prints in bold colors, thin spun cotton, not the luxurious thick fabric—that’s for the American market. In these giant wholesale plazas that feed everywhere in the world, you can see starkly where Nigerian fashion falls in the global hierarchy: the bottom. In the factory Kingsly scrolls through images on his phone, googled or sent from his contacts in Lagos. He gestures to his own shirt, demonstrating how he wants to adjust it: adding a cuff link or changing the neck line. He speaks a few words of Chinese, but he also relies on a translation app.

When the orders are complete he brings them back to the plaza where he has a skeleton shop. Just a few designs are suspended on the walls, for Africans who travel on brief trips to buy stock. Most of his goods, though, he ships directly to Lagos. One by one he pulls out the shirts, ironed flat and enclosed in plastic, and puffs the lining like a balloon. He said they sell better in volumized bags, even though the shirts are the same.

There have been recent crackdowns on what China considers a “floating population”, and you can see it in the faces of the Nigerians there. In the plaza, Chime half-watches, disinterested as Kingsly stuffs his shirts into giant mint green satchels for shipping. Worried about suspected surveillance, he is laying low, loitering until late at night to avoid going home. When he leaves, he skirts the African hotspots in the city, like the Tong Tong Hotel, a plaza with wax print and Versage spilling onto the street beneath a gleaming Neon sign advertising the African-Pot Restaurant upstairs. Police officers are often stationed outside, checking passports and visas.

Still, for all the challenges and the instability, the Nigerians stay in China. Their role in the Versage supply chain is essential, because the fashion is infused with taste and personality. The Nigerians in China are the translators, and curators of taste: Chinese don’t understand what Nigerians want, they all say.

Whether they are designing clothes and ordering them, or scouring markets to buy stock, each bale, each shipment, each entrepreneur has a slightly different flavor than the next. It’s what makes fashion a risky, but creative business. While from the outside the thousands of small shops in Balogun bleed together into one overwhelming aesthetic, plywood extensions covered in a tapestry of swirling medusas, on closer inspection each shop has completely different stocks.

Once a look arrives in Lagos, there can be a swift mimicking among the other purveyors of taste. Suddenly the boys watching the streets in Lagos are calling their brothers in China telling them to build on the latest evolution of the aesthetic. But the first one with a hot look can earn a windfall. This leads to intense secrecy and competition between vendors. Chike, a Versage designer jealously guards his creative process: “Before I show somebody my design I must sell more quantity because they might copy it,” he said, unperturbed by the irony of protecting his own copy from other would-be copiers. This is because he is a knock-off designer, oxymoronic but true. The competition and evolution of the market is all among “creative copiers.” His designs are his own designs. “The idea, business is secret,” he said.

There is a lack of trust at every step of the Versage supply chain, what Nigerian economist Kelechi Deca terms a “trust deficit.” Grossman expanded on the sense of distrust that permeates the trade: “in my mind there is not necessarily a trust deficit in the sense that there is no reason you should trust those people…actually you have a good reason not to be trusting.” Informal deals leave traders with little recourse if things go awry. This is partially why traders still travel, to verify what they are ordering. Every entrepreneur I spoke to, from street hawkers to factory owners had a story of getting cheated. Chibuzo invested in a shipment of shoes that disintegrated before they arrived in Nigeria. A fake visa agent stole KC’s money and conferred nothing. Many of the traders travel to China after some kind of business catastrophe at home. They need a fresh start, a fresh opportunity and they hope China can offer it. But few of them plan to stay long-term. They stay intricately connected to Nigeria. After seven years living in China Chibuzo still keeps Nigerian time, sleeping in the wee morning hours and waking midday in Guangzhou. Everybody texts him in the middle of the night, he said, and his clients are following market hours in Lagos and Aba.

When an order is rushed, Chibuzo ships his goods by air. Not DHL or Fedex; he connects with Africans flying home from Guangzhou and buys the right to their baggage weight. The traveler charges $4 or $5 per kilo, which helps offset the price of the ticket. This informal shipping system is an expensive option for thesender, so most clothing is sent by cargo. It takes 6 weeks to arrive in Lagos. Containers stacked with cheap shirts float across the ocean then queue at the port for offloading.

Some of the goods go through customs. Some of the goods are banned. They still go through customs, they just cost a bit more. “It just means it’s more expensive for people to import it, they still do,” explained Vivian Chenxue Lu, a doctoral student at Stanford who researches Nigerians who travel for business. “They would have to pay off customs officials…I think it makes it more risky, like if [border agents] were in a bad mood they could just take all of it.” Bans make for more complex power dynamics to navigate, more risk, more possibility for exploitation. The cost trickles down to the consumer, but bans don’t really affect the supply. Imported shoes, for example, are banned in Nigeria. But Balogun market is full of them: slippers, stilettos and sneakers.

The Kick Against Indiscipline (KAI) Brigade cracks down sometimes, confiscating traders’ goods, though they tend to monitor for illegal vending practices, not the goods themselves. In the springtime there was a wave of crackdowns on hawkers in Balogun market. KC always stood above a pile of t-shirts facing the Kuti Mosque, one in a line of vendors sweating in the direct heat. Behind him money changers had set up shop on some benches. The intersection was crowded and abuzz, it was often hard to pick him out of the crowd. But one day I came to see him and the whole area was cleared, bare and barren. When I called he said he was home, sick with malaria. Or maybe it was depression. When I next saw him at the market he didn’t have his goods anymore, he was guiding would-be shoppers up the rickety staircases to shops, hoping to make a sale and scrape a bit of profit off the top. He said KAI had come and confiscated his wares, part of an ongoing crackdown in the Central Business District. But even this is semi-formal. The KAI truck is often at the market, and police officers are often lounging inside, their feet on the dashboard. The hawkers work around them, keeping one eye on the truck for movement. It’s only when the raid begins that they clear out. Even if they are caught, only some of them follow the channels to the station, to prison, to the official fee. Others bribe their way out of it, and go back to their trade.

“The traders I work with they talk about it as anti-Igbo bans basically because it really just affects their livelihoods in particular because they’re the ones trading, they’re the ones importing,” Lu explained. She says that most Igbo traders link their emphasis on business to the civil war and discrimination that they feel limits their participation in other sectors. “None of my informants, the people I work with dream for their children to be traders…they see business as a path for upward mobility so they would like their kids to go to good schools and do something else with their lives. So Lagos isn’t just a place where there is money.” Igbos face stereotypes of being rapacious, or money-obsessed, unattached to Lagos aside from its commercial potential, but Lu has found a more complex story in her research. The concept of home is not always black and white. “When they talk about Lagos they estimate that it’s 50% Igbo and it just reflects the part of the city that they live in,” Lu said. A city is a stack of millions of distinct worlds; each denizen lives a unique experience. “There are a lot of social opportunities... Lagos is still central for West Africa, and people, a lot of people I work with have lived in Lagos their whole life and the village is where they go for holiday or when it’s unsafe…I don’t think that means they are not invested in this space as a Nigerian space.”

Informal business in Lagos is risky. You are investing in yourself, with yourself, moving yourself: between cars, between countries, between legality and illegality. Traders call Versage "casual" and explain earnestly that people won't wear it to the office. But again, two thirds of the economy in Nigeria is informal. Most young men aren't going to an office. Most young men in Lagos are street entrepreneurs of various levels. And Versage is their uniform: a costume that asserts taste, style, dignity and aspiration.

The names of some traders have been changed to protect their identity.

[gallery]