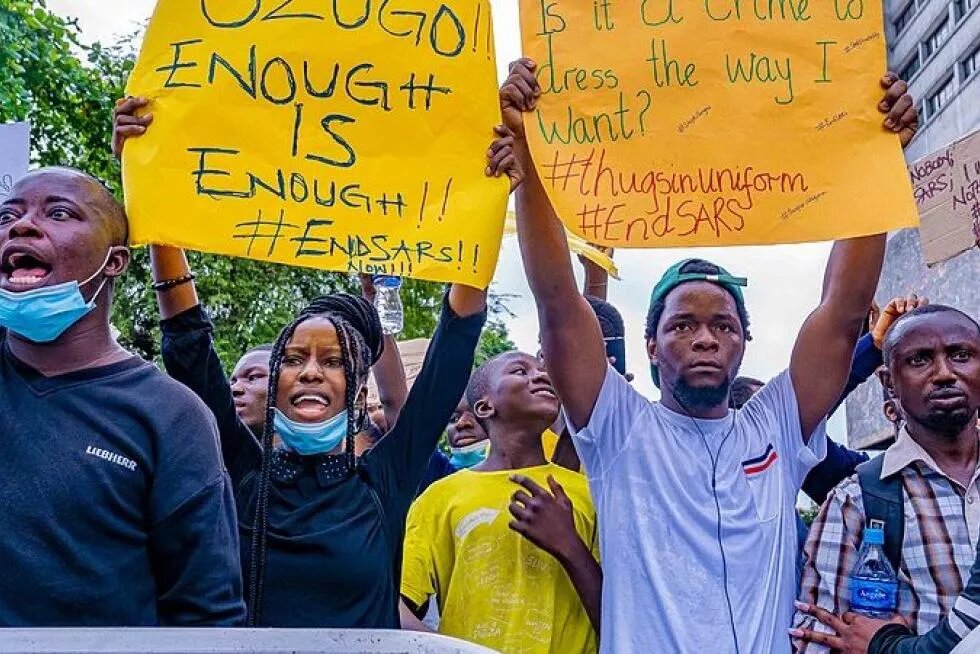

Nigeria has rarely spoken with one voice, but the relentless police brutality has given this new generation the opportunity to find their voice, loud and determined.

Looking back over the last few weeks, one is overwhelmed by the sense of the tragedy that has befallen Nigeria during the #EndSARS protests and its aftermath. This is not just about the number of lives claimed by bullets fired by police officers or soldiers, or the machete and cudgels of sponsored thugs. One could argue that greater numbers are lost in a day in bandits-infested villages of northwest Nigeria.

Nigeria’s face is scarred by many ancestral gorges that nationhood, imposed by the British in 1914, has not healed. And judging from recent events, may never paper over. On very rare occasions has the country spoken with one voice, not once in this generation. Until recently—to a large extent.

Who knew it would take recalcitrant police brutality for this generation to find its voice. When it did, it was loud and tenacious. Amplified on social media, it became global and reverberated in the cold hearts that govern the country. And it lingered. Longer than anyone had imagined, longer than those who have mastered the art of keeping Nigerians in perpetual subservience have experienced. Perhaps longer than was necessary. For a generation that has been dismissed as being more obsessed with watching Big Brother than protesting petrol and electricity tariff hikes, it came as a surprise. It was the hint of an awakening that is wonderfully terrifying. It would have been naïve to expect this government—one of painfully old ideas, where any exist—to stand by and watch this voice grow.

Of course, it was easy for the government to fracture the narrative, to create a delta of meaningless streams out of a great river that threatened to sweep away some of the rot and the old chains that have held down this country.

Those chains are old but they have endured for a reason. The #EndSARS protests was a mass movement but it wasn’t popular in the north, where the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) has not been as brutal as it has been in the south. It has, in fact, helped in fighting Boko Haram in the northeast. At the height of the #EndSARS protests, in Maiduguri, where Boko Haram was founded, a coalition of civil society organisations even protested in support of SARS. Governors of the 19 northern states, absurdly, demanded that all SARS officers be deployed to their states because they would very much love to have their services.

There were whispers too. Rumours of the protests being aimed at Buhari, of a political machination to either remove him from office or destabilize his government. This may be farfetched but many in the north, where Buhari enjoys cult-like following, believed this. Somewhere in the fertile imagination of these people, the idea that the protests’ ultimate aim was to dislodge Buhari from power took roots and sprouted.

The same northerners who had eagerly rioted in 2011 when Buhari failed to win elections that year suddenly started preaching that protests—even if the protesters were orderly and peaceful— were unhealthy.

With the fervour they argued, one wonders if this Buhari these people were keen to defend was not the same one who had looked on, nonchalantly as bandits raided villages, killed hundreds and displaced thousands; the same Buhari who has, in five years, also failed to end Boko Haram in six months as he had promised during his campaigns.

Mistakes were made on both sides, no doubt. It was puzzling to see the failure of an entire region to understand that agitations for good governance, which is what the #EndSARS protests was eventually morphing into, would be in the best interest of everyone, north or south. At the same time, protesters failed to realize that they are pushing against frayed nerves, even after the government, surprisingly, had acceded to their demands.

The thugs, mostly northerners, who allowed themselves to be used to attack protesters in Abuja and the northern city of Kano and elsewhere were convinced by anti-Buhari conspiracy theories but mostly by the token they were paid by persons acting to undermine the birth of a significant moment in the history of this country. It is a move plucked from the textbook on how to keep a people divided to hold perpetual power over them.

On Tuesday, October 20th, something happened at Lekki Toll Gate in Lagos. Soldiers shot into protesters kneeling on the ground, waving the Nigerian flag and singing the country’s anthem. Some described it as a massacre—even if after a week, the fatality rates are far fewer than initially thought. In another move taken from the well-thumbed book on suppressing dissent, the military, despite issuing threats to protesters days before, denied being responsible for the shootings. Since then, the position has shifted. The military confirmed it had boots on the ground, invited by the Lagos State Government, which has denied it ordered soldiers to shoot at protesters.

Whatever happened that night at Lekki had the same effect as using a hedge shear to crop off the wings of a butterfly. What becomes of a butterfly without its wings?

The shooting that night reversed the evolution of the #EndSARS movement, and the fledgling butterflies of that protests that rekindled hope in our nation have regressed to caterpillars. They have been doing what caterpillars do—feasting, indiscriminately. The orgy of looting that followed has seen desperate people and rogues breaking into warehouses and pillaging foodstuff meant for the public during COVID-19 lockdown, which government officials have been hiding. We may want to justify this as people taking what is theirs, as exposing the level of corruption and the sheer wickedness of government officials who have kept this much-needed food supply from the poor people they are meant for. However, it would be wise to remember also that the problem with caterpillars in a feasting saturnalia is they do not distinguish weeds from crops. The lootings have since become an opportunity to steal from private businesses and homes, and for general lawlessness.

The regression of a well-intentioned protest that was birthed by people who picked up their thrash and binned it has seen vandals and rascals, first unleashed by the government, running wild. They belong to everyone and they belong to no one.

Whatever mistakes we see in this, we must not forget that those who trucked in thugs to attack protesters and those who pulled the trigger that night at Lekki, prompted this chaos.

Though the sounds of those rifles are infinitely louder than the human voice. But a bullet, as history has amply demonstrated, can never outlive an idea. And though Lekki might have killed Nigeria in the hearts of many of my countrymen and women, in the hearts of others, seeds of ideas the protests have tucked into those fertile hearts will sprout into something. It might be wondrous or horrendous, I am not entirely sure yet. What I am certain of is that something is going to grow out of it.