The Geneva Refugee Convention – officially known as the “Convention of 28 July 1951 relating to the status of refugees” – turned 70. Hardly anyone feels like celebrating in view of the many violations internationally, but the occasion offers the opportunity to strongly support the Convention’s principles in face of all hostilities, because it stands for nothing less than the protection of refugees.

When, as in Australia or the USA, at the Croatian-Bosnian border or in the waters off the Greek islands, refugees are brutally pushed back, even imprisoned in detention centres on islands far from the Australian mainland, then the promise of 1951 to grant protection to persecuted people, to give them rights as well as obligations, is broken. Yet there were good reasons for this promise, especially in Europe after the Second World War. How many persecuted Armenians or Jews could have been saved if the status of refugees had already been clarified and the promise of protection had been offered?

From 1951 onwards, protection initially applied to those who had to flee “as a result of events occurring before 1951” and remained related to Europe. New refugee crises in the 1950s and 1960s, however, made it necessary to extend the temporal and geographical scope, which is why a protocol to the agreement was drawn up and adopted. The “New York Protocol” called on all countries throughout the world to share the promise of the Convention.

It can be claimed, of course, that the Geneva Refugee Convention (GRC) and also the New York Protocol have become outdated. The scale of global displacements and migration is too great, too many intertwined problems are desperately asking for solutions. The routes are taken by a mix of people who leave their homes for different reasons: migrants in search of a better life, refugees hoping to escape famine or natural disasters, as well as many others who fall outside the narrow definition provided by the Convention. There are several aspects about the Convention and its evolution that are problematic. And obviously things gp fundamentally wrong when migrants in search of better lifes apply for asylum because there are no other possibilities for them to stay.

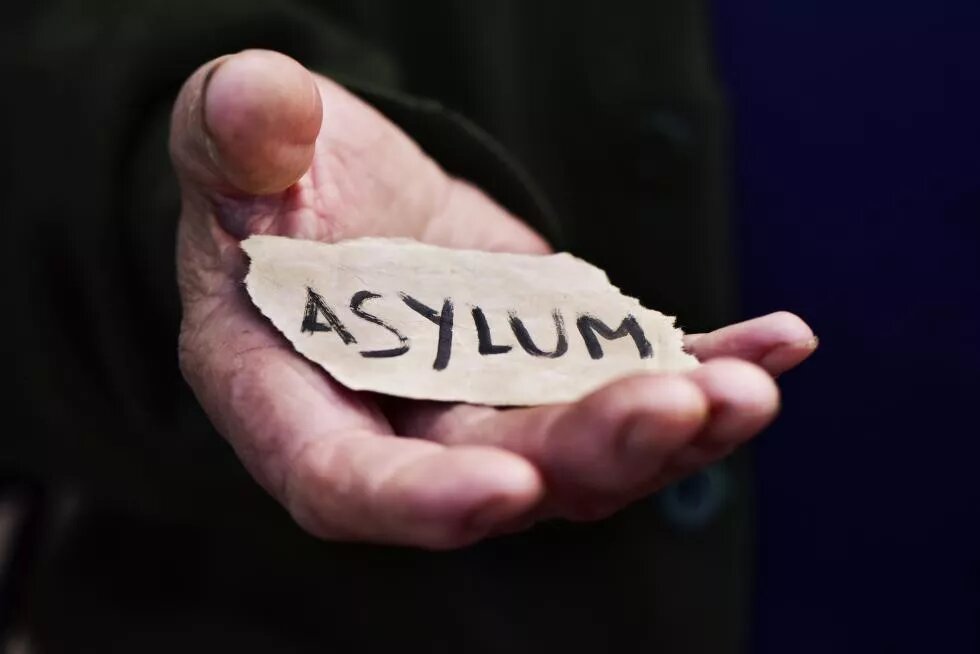

Nevertheless, the Convention is indispensable. It provides the foundation for international refugee law. It defines the term refugee and sets minimum standards for the treatment of refugees. Particular importance is attached to the principle of non-refoulement, which establishes an individual’s right to be protected by signatory states from being returned to a country where they would risk persecution. Let us respect these core principles of the Refugee Convention and examine carefully who wants to remove them. European politicians from Greece to Denmark – not to mention Hungary or Poland – disregard the Convention and its principles when it comes to “managing” the “refugee problem” on their own doorsteps, thus emulating the Australian government, which since 2013 has developed its “Operation Sovereign Borders” policy into one of the strictest deterrence regimes, with boat “pushbacks” and detention centres on offshore islands.

What do these core principles actually say about ourselves and our societies? What happens to us when we offer protection to those who have been left without protection in their own states, who have been persecuted and forced to flee? What have we learned in Europe from the experiences of the Second World War? How humanely do we act and how do we enable those in need of protection to live a decent life without discrimination? Insisting that refugees seeking protection should not be turned back in no way implies a call for open borders.

The Convention and its protection of refugees remains just as indispensable after 70 years as it will do in the decades to come. Let’s ensure that more states are committed to the principles and implement them. Let’s equally ensure that the ever-growing global refugee crisis is borne by many shoulders.