Innovation, creativity and financial power – Lagos has all the necessary ingredients for a thriving startup sector. Hackathons, boot camps and startup weeks regularly attract local and international participants. Ayodeji Rotinwa, a freelance journalist, asks himself whether these are signs for a healthy growth potential.

The beginning of the hype around start-ups in Lagos

Around 2012, two Harvard Business School graduates, Tunde Kehinde and Raphael Afaedor with stints at Goldman Sachs and Diageo and experience at tech startups abroad, returned home to build something on the African continent. To help the “dark horse in the digital revolution” come out in front in the race. To be part of “Africa Rising.”

They co-founded Jumia, today a Nigerian e-commerce giant that brings your shopping wants, needs and desires to you. You need a cashmere shirt to wear on a special date? You could order on your phone while chatting to your loved ones wondering what colour might catch their eye. Tired of being hunched over your desk? You could order a back brace from your work laptop while pressing your hand to the pain in your lower back. The e-commerce site became wildly popular. It ran its operations from 20,000 square feet warehouses in Lagos. It attracted millions of dollars in funding. It was the example of what was possible in the city’s nascent tech ecosystem, and an example for others of what to aspire to. Other startups across different sectors - but especially e-commerce sites - started to quickly mushroom and attract some funding from international investors. Tech hubs and accompanying industry events - hackathons, pitch competitions, demo days, investor networking parties - became more common over the years. Collaborative workspaces were declared “the future of work”. They exist in different corners of Lagos now.

Lagos became known as a hotbed of innovation, an inspiration for other tech communities across the country, and perhaps the continent. In 2017, the global business publication Quartz African reported that Lagos was now the startup capital of the continent, being the epicentre of the tech industry and raising $109.37m in funding, more than any other country. It is here that the seed of Nigeria’s economic revolution is supposedly being watered.

The thing with a perfect picture, however, it is often too good to be true.

I’ve often wondered what was wrong with this one. Is the hype about startups real? Is it sustainable? Why do we never hear of their failures? Are they somehow operating above Nigeria’s formidable infrastructural, political, economic, problems? Are they making a dent in the economy and are they being enabled to be Lagos and by extension Nigeria's ticket to economic nirvana? More so, the Lagos state government claims it has a mega city agenda that has been in motion for almost two decades. Is the tech sector a part of this agenda? Is the support it currently offers enabling the sector as advertised? Is it even enough?

In the early 2010s, the trendy businesses were the e-commerce ones like Jumia, and also Konga, Supermart, Gloo NG selling groceries, appliances to anyone who would download their app or log in. For a time after that, it shifted to agritech and edutech, with startups springing up to take advantage of the legion - often logistical gaps - in the agriculture and education industries.

Agritech startups are seeking to solve the logistics of food waste in the country, how to best get produce from the farm to the end consumer in the most efficient and effective manner. Some also create solutions for farmers to access credit to grow crops connecting urban citizens with some disposable income with rural farmers who need the cash injection to expand their production.

Edutech startups make learning more accessible, and quite frankly, competent. Students are able to study for required examinations with curated curriculums that are often more up to date than what is offered in schools, public or private.

These days though, the tech startup darling is fintech: companies building payment systems and allowing businesses get paid; helping customers save, acquire credit, and partake in the global economy of buying and selling with digital money solutions. Given the country's - thankfully waning - reputation for internet fraud, local bank cards often do not work for international transactions. Fintech startups create solutions for Nigerian customers to pay for foreign products.

Are any of these startups succeeding?

By all indications – according to information they choose to share publicly - it appears the fintech companies seem to be doing very well. The reason is however not farfetched. All other sectors rely on fintech companies to solve the problem of payments for them to be able to thrive. No matter how innovative an edutech company is, if it cannot collect payments from customers, it would ultimately fail. Notable in the fintech category are Paystack and Piggybank.

Paystack helps small, medium, big businesses and people accept payments via credit, debit card, mobile money, money transfer via websites or telephones. Over five rounds, since its creation, the company has raised $13m and announced recently that it now does a volume of 1 billion transactions monthly. Things are going so well, the company announced it would be expanding operations to Ghana very soon.

Piggybank, founded and run by Covenant University graduates in their 20s who are serial entrepreneurs and have started a number of businesses between them, helps young Nigerians save. Recognising that the current banking system is not built to help people was what inspired the creation of the startup, Odunayo Eweniyi, one of the co-founders explained to me.

The average savings account in a Nigerian bank gives you ATM cards, withdrawal slips for an account you are supposed to use for saving money. You earn insignificant interest at best. Piggybank connects to your bank accounts allowing you to save little amounts daily, weekly or monthly as you choose towards set financial goals. I currently use it. Instead of saving huge chunks of money - unsustainable in an expensive city like Lagos - Piggy Bank painlessly deducts a set amount from my account daily that counts towards my rent, travel expenses. Sometimes I don't even know when the money goes. Piggybank has also raised in excess of $1m dollars from a consortium of local investors who reached out to it, Eweniyi told me in her office nary a hint of cockiness or self-satisfaction. For context, local investors are not going around - yet - investing that kind of money. When they do so apparently, it’s a secret affair. Eweniyi would not tell me who her local investors might be.

Weak support by incubators, accelerators and investors

Experts did tell me e-commerce these days is a no go for investors because it is ultimately too capital intensive and difficult to run. With rent in Lagos reliably astronomical, cost of moving goods around, rising costs of fuel to do so, it seemingly does not make businesses sense. Konga - Jumia's competitor - and another large e-commerce site failed earlier this year and was bought over by another e-commerce site, Yudala for $1. It simply ran out of cash. Jumia for all its might is supported by other ancillary services which provide travel or property listings alongside its major e-commerce offering. Six years after operating, there are speculations it has not yet broken even.

Presumably helping to clear the path to success for startups are the innumerable tech hubs, incubators, accelerators, investors, some local, most international, operating in Lagos who provide much needed technical know-how, mentorship and funding. Paystack, for instance, was accepted into the most prestigious incubator in the world, Y Combinator which has been instrumental in its scaling the challenges of raising funding. It is not yet clear whether homegrown incubators are able to muster such might.

In an ideal situation, incubators in Lagos would provide early-stage support to startups. Their doors would be open to even startups that have just an idea, not a product. They would help startups finetune the idea, the product and eventually a business model.

Accelerators would focus on startups in their growth stages and who are ready to expand to connect them to investors. Venture Capitalists ideally would be interested in startups who have proven themselves to be viable businesses, who have started making revenue, and who need a cash injection to boost them to the next stage. But this is not necessarily the case in Lagos, according to the experts I spoke to.

“Such support organizations are essentially startups themselves. A case of the blind leading the blind,” an investor and venture capitalist who wishes to remain anonymous, said.

“Historically, I don’t think there were enough expertise and access in local incubators and accelerators to add value to founders participating. Things are changing now. What we see as a more effective model is founders going abroad for specialized accelerators and then returning home.”

There are not enough incubators in Lagos providing early-stage support to startups. Part of early teething problems startups face is access to market, finding customers for their product or establishing that potential customers need the innovation they have created. Currently, only three spaces, Passion Incubator, Wennovation Hub and Leadpath Nigeria, provide this service in a city where there are close to 1,000 startups.

Instead, there is a proliferation of demo days, hackathon activities, co-working spaces, who provide similar offerings to all start-ups but the foundational work in building these startups to become viable businesses are missing. Most of the Nigerian accelerators were built on the Silicon Valley model going in for intensive mentorship, training the startup for 3 months and leaving with the hope to immediately raise funds to grow their business.

“There is no pipeline of funds in the Lagos startup ecosystem”, Chika Nwobi, told me. He used to run an accelerator called 440NG that has since shut down. Funds which mature startups needed to grow their business to the next stage are simply not available. Instead, incubators and accelerators have ‘experts’ advising startups on any myriad range of issues, no matter the sector, from health logistics to financial services which are by nature two starkly different beasts.

“There should be sector-specific accelerators in the ecosystem, not ones addressing all the same issues and are horizontal,” Eghosa Omoigui, Founder of Echo VC, a leading investment firm, told me.

This means startups providing financial services, for instance, should have accelerators dedicated exclusively to that sector. The sector is seeing this happen slowly with financial institutions like Stanbic IBTC (Blue Lab) and Access Bank (Fintech Foundry) setting up accelerators for startups building products and services in the finance sector, that could also be useful to their overall business. These accelerators are run by people who have years-long expertise in their field and are run by a company that has to prove its success to its shareholders and just can’t write it off as a Corporate Social Responsibility.

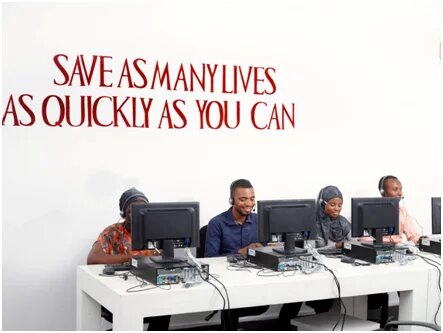

The most prominent incubator in Lagos is CC Hub, founded in 2010, visited by Zuckerberg and seen as the epicentre of innovation in the tech ecosystem. I went through the CC Hub website and analysed the 26 startups it listed. If success - using the ecosystem’s own metric of funds raised and some announcement of expansion is what we might judge success by - then my answer is the Hub has had only one breakout success in 8 years: Lifebank, a logistics health company that facilitates the delivery of much needed blood, oxygen and other medical products to hospitals. In its last funding - publicly announced - round, it raised $200,000.

Who succeeds in raising funds and where is the money coming from?

The short answer is (mostly) male startup founders, especially those with international partnerships, connections or networks. Most of the money is coming from foreign investors.

According to angel investors and venture capitalists I spoke to, the demand for funds still outweighs supply hence why some local investors make investments in secret so as not to be inundated with requests for funding. And startups with repatriated founders stand a much better chance of receiving funding from foreign sources which are still the largest source of incoming investment, although local knowledge was still required to guarantee success.

“It is not unique to Nigeria that investors favour foreign trained entrepreneurs. Homegrown guys are at a disadvantage because their education system does not expose them. To raise international funding, you need someone who can speak their language, speak to processes, conceptual models,” Tomi Davies, co-founder of the Lagos Angel Network and the African Business Angel Network both consortiums of individual investors in the tech industry.

Take a real-life scenario of Davies’ assertion, the tale of two companies offering similar products: pay-as-you-go off-grid renewable energy. RenSource was founded by Ademola Adesina, a German-based Nigerian who studied abroad and has worked for global organizations in the USA, United Kingdom such as JP Morgan, The Rockefeller Foundation. Over three funding rounds, his company has raised $5.2m. His co-founder is a western national.

Arnergy was founded by Femi Adeyemo who got his first degree in Computer Engineering from the Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Akure Nigeria. He has only local working experience. Though lauded as innovative and groundbreaking his solar business has only been able to raise $146,000 in comparison from a grant fund by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID).

Rensource has existed for three years. Arnergy has existed for four.

A number of Nigerian startups succeeded in joining Y Combinator programs and then went ahead to raise money in varying stages of their business, they likely would not have received locally or at all. After its graduation from Y Combinator, the low-cost internet service startup Tizeti was able to raise $3m recently from different investors. Kobo360 a logistics company, that connects truck drivers to companies with freight needs, raised $1.2m.

Women, however, are not securing funding in any equitable metric to men. There are not many female startup founders, to begin with. Bankole Oluwafemi of TechCabal suggests that there is no concerted effort to encourage women to become tech entrepreneurs. Olumide Soyombo, a co-founder of Leadpath Nigeria, a local incubator, stressed that his incubator had funded female-led startups but the startups were usually in businesses marketed towards women like fashion, baby products. Temie Giwa-Tubosun, founder of Lifebank thinks that if she was a man, she would have likely raised money faster; investors routinely seemed to doubt her ability to run a “difficult” health startup. Odunayo Eweniyi of Piggybank had the experience that “local investors related better with men” when her company tried to raise money. She has two male co-founders and had to make the decision to stop attending investment meetings, just so her company could get their foot in the door. Chika Nwobi of L5 Labs, a local venture capital, citing cultural restraints admitted: “I am unlikely to mentor a female tech entrepreneur because I am married.” He explained that cultural beliefs stopped him from developing a close but professional relationship with female tech entrepreneurs because it could be easily misinterpreted.

Because of this gap in the market, a number of initiatives are dedicated specifically to female tech entrepreneurs to receive funds, industry expertise, mentorship and support: GreenHouse Labs, is a program by the Venture Garden Group (VGG) focusing on financial services startups. Nichole Yembra, Chief Financial Officer of VGG said, “Our mission through GreenHouse Lab is to build world class, women-led technology companies by equipping entrepreneurs with the skills, resources and support needed to rapidly grow and scale their companies in emerging African markets.” It currently has nine startups in its cohort who will be pitching for local investment at the end of the program.

The city government’s support has been missing so far

Tosin Faniro-Dada, the Head of Lagos Innovates the startup department of the Lagos Employability Trust Fund (LSETF), admitted that the startup scene had been somehow working without any kind of government support. But now the government seeks to accelerate its progress through a number of ways. It has a workspace voucher program that pays for office space for qualified startups at tech hubs or co-working spaces; however, the vouchers are only available for a limited period of three months to a year, depending on the growth stage or needs of the startup. One interviewed startup founder judges this as not sustainable because “what happens to the startup when its voucher expires and it still needs office space?” Ideally, there should be a minimum amount of one year given to all startups.

The Lagos State agency also provides loans for co-working spaces to incubators and accelerators who support startups up to a maximum of N50m per space, for over four years at a 9% interest rate; according to Faniro-Dada this is “the lowest in the market”.

Government plans to kick off capacity building programs before the end of 2018 for underemployed and unemployed Lagosian residents teaching technical skills and software or web development courses for building tech products. The program is expected to run for three months and will be in partnership with a training company that will be responsible for placing attendees in jobs post-training. An accelerator program is also in the works, in partnership with an existing accelerator that should invest directly and develop or contribute to a Fund that will invest in startups.

My conclusion what from I have learned over the course of my conversations and research is the hype does not justify what is on the ground.

First, the government should definitely be doing more. If it truly intends to support, enable and accelerate the startup scene, then it should be its number one customer. As is, when it comes to public procurement, the criteria by the government is often so astronomical, that nascent tech businesses cannot hope to compete. Yet the government will benefit so much from digitising its services, tax collection for instance. Data science could also be possibly applied to the city’s gargantuan transportation problems. But apparently, the government is only happy to provide piecemeal solutions.

“We prefer to be partners and not customers,” Kunmi Adio-Moses, Deputy Head of Lagos State Office of Transformation, Creativity and Innovation. (OTCI) told me. He explained that the state government has a policy where it would rather partner to provide services to the wider public, rather than pay or hire startups itself.

Second, the fact that most startups have to rely on outside sources for funding means foreign partners will indirectly dictate the startups being created, influence the problems being chosen to be solved. This likely means that startups are being created to raise (and earn) money and not necessarily solve local problems first. Also, increased funding by foreign partners is not necessarily a reflection that the startup scene is growing, It ultimately pays foreign investors that payment systems in foreign markets work, so they can sell to those markets and collect money from them. Perhaps not necessarily a bad thing in itself - we live in a ruthlessly capitalist world after all - but this is connected to my previous point. In addition, these big-ticket investments are not coming consistently and in a sustainable manner to be pointed as a mark of growth. For every startup raising millions of dollars, there are hundreds starved for cash.

Third, and finally, ultimately, the Lagos startup scene is still very much at an early stage. The tech hubs need to be more organized to provide support to the startups. Startups need to share knowledge and information amongst themselves and create spaces for others to learn from practical experiences and failures. Else, it might take a while still for it to run as efficiently and sustainably as it should.

For now, hype is not a strategy.