Nigeria is well known for its oil wealth, but the agricultural sector is the backbone of the country’s economy. In 2021, agriculture accounted for about 26 percent of the gross domestic product, compared to oil and gas (7 percent), manufacturing (9 percent) and trade (16 percent). About 35 percent of the active labour force is directly employed in agriculture.

However, the sector faces major challenges. It needs to feed a rapidly expanding population in a warming climate characterised by increasingly frequent floods and droughts that reduce soil fertility, while parts of the country remain in conflict, ranging from the Boko Haram crisis in the northeast to farmer–herder clashes in the Middle Belt. The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic and the impacts of the war in Ukraine on global energy prices have further exacerbated food price inflation.

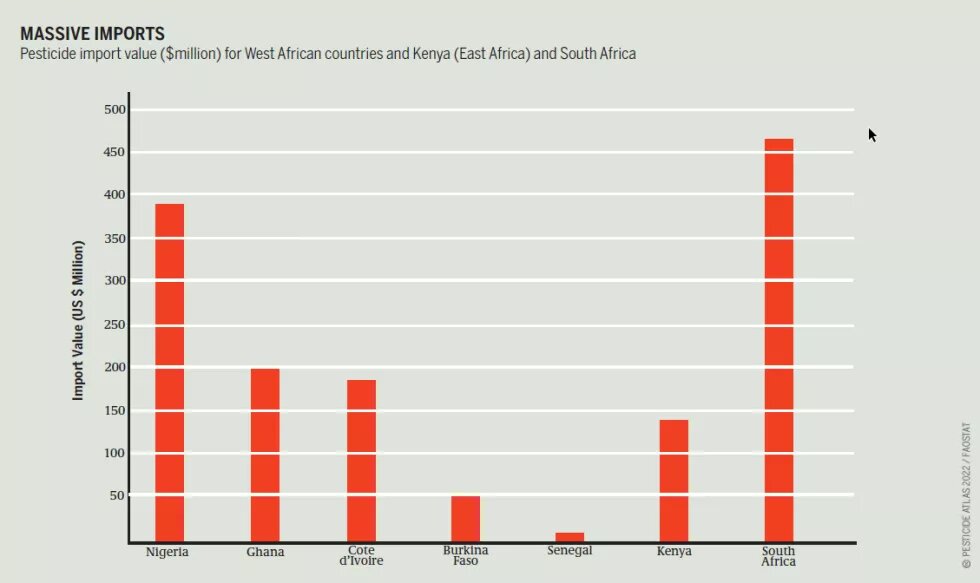

The country is currently unable to meet its domestic requirements for food as population growth has outpaced the rate of food production. According to the United Nations, the number of people living in Nigeria is expected to almost double by 2050 from its current level of just over 200 million, fuelling greater consumer demand for food. Government policies have therefore focused on increasing productivity. These mainly promote conventional agriculture that requires a high degree of external inputs, such as pesticides and artificial fertilisers. However, the use of pesticides has resulted in negative health, environmental and economic consequences in Nigeria.

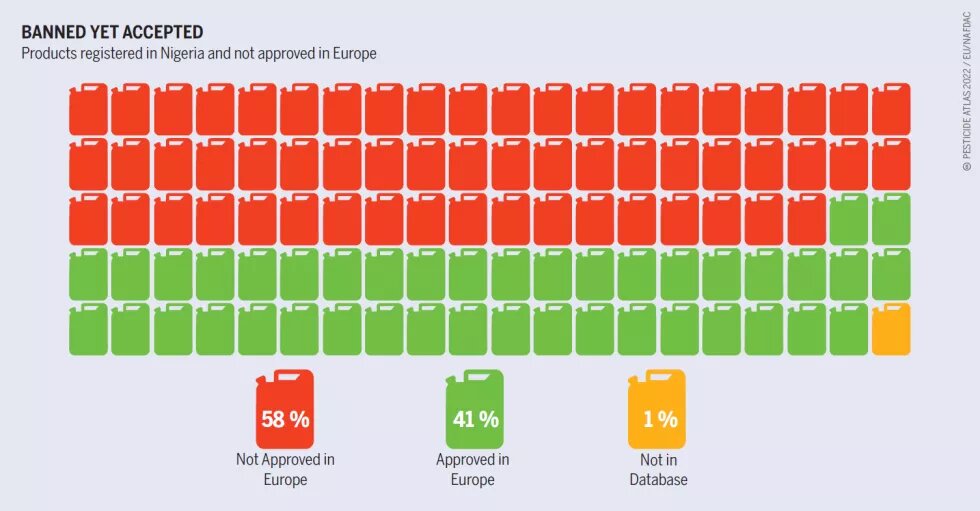

The registration of pesticides in Nigeria is covered by the Drugs and Related Products Act (1996), the Pesticide Registration Regulations (2019) and the Guidelines for Pesticide Registration. The National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) is the registration body and also regulates and controls the import, export, manufacture, advertisement, distribution, sale and use of chemicals. As at November 2022, NAFDAC's Green Book product database lists 682 synthetic chemical pesticide products (excluding chemical repellents). More than half of these products include active ingredients that are not approved in the European market due to, for example, their potential chronic health effects, environmental persistence, high toxicity for fish or bees, or insufficient data to uphold the principle of preventing harm. NAFDAC is reviewing registered active ingredients with the intention to phase out some of the most hazardous substances – including ametryn, chlorpyrifos and methomyl – and to reclassify the use of a few others. The outcomes of this process are yet to be published.

Surveys have shown that 80 percent of the pesticides used most frequently by small-scale farmers are highly hazardous pesticides. Among the most commonly used are atrazine, chlorpyrifos and mancozeb – all of which are prohibited in the European Union.

Nigeria has missed important export opportunities because of the high use of pesticides on farms and during storage. In June 2015, the European Union banned the import of dried beans and other Nigerian agricultural products that contained levels of pesticide residues considered dangerous to human health. The United States has similar bans in place.

The use of these substances also impacts the health of the Nigerian population. Although the Nigerian government does not systematically collect data on pesticide poisonings, there are regular media reports of such incidents. In 2020, more than 270 people died in Benue State after drinking river water poisoned with Endosulfan, a pesticide that was banned globally in 2011 under the Stockholm Convention, including in Nigeria, but is still available in Nigerian markets.