Africa is quickly developing a dependency on agricultural pesticides. Increasing farm labor costs and pressure to intensify land productivity as well as greater availability of internationally manufactured, inexpensive products are some of the factors driving increased use on the continent. However, most African governments do not have adequate resources to monitor the impacts of pesticides or the capacity to prevent negative human health and environmental consequences. The widespread adoption of pesticides means that millions of smallholder farmers are exposed to the risks associated with using these chemicals on their farms.

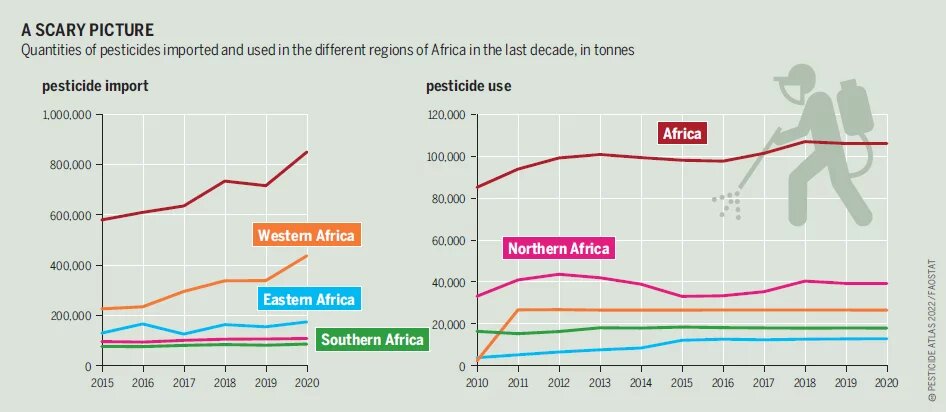

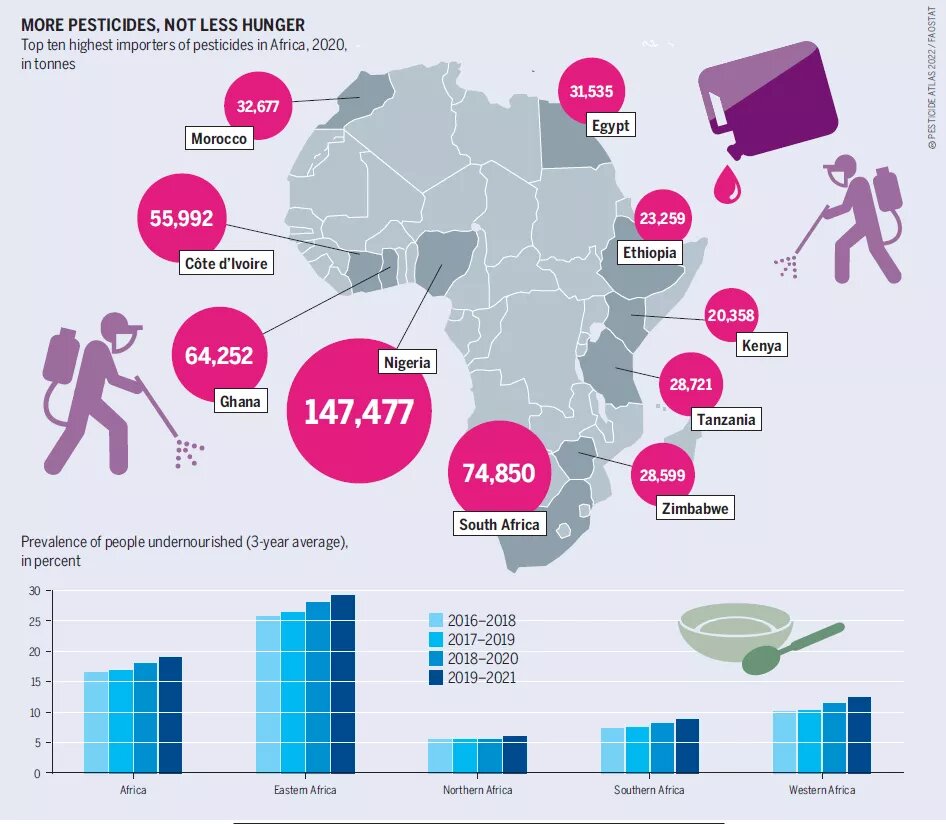

Over the last five years, pesticide imports into Africa have increased signficantly. In West Africa the imports have doubled in five years from 218,948 tonnes in 2015 to 437,930 tonnes in 2020. In 2020, Nigeria’s imports alone (147,446 tonnes) exceeded the total imports of Southern Africa (87,403 tonnes) and North Africa (109,561 tonnes). Despite increasing imports in these regions, the informal nature of agricultural production has made it difficult to record how pesticides are used hence the big differences between the imported quantities and use data. For example, in 2020 the FAO recorded the value of imports in Southern Africa at 87,403 tonnes, compared to 27,000 tonnes of pesticides that were used.

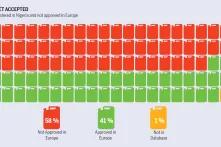

New traders and business people with limited knowledge about pesticides are taking advantage of the situation. There has been a proliferation in the illegal trade of counterfeit products which are smuggled through porous borders. Counterfeit pesticides are not authorised for sale by the mandated pesticide authorities and can lead to a total loss of treated crops, compromising farmer livelihood. In addition, counterfeit pesticides might contain chemicals that are either banned or restricted. Regulators are usually caught unaware when produce from their countries includes active ingredients that they have not approved.

According to the FAO pesticide use data from 2020 and in terms of leading countries in each region, South Africa leads in Southern Africa (26,857 tonnes), Egypt in North Africa (11,352 tonnes), Cameroon in West Africa (7,322 tonnes) and Ethiopia in Eastern Africa (4,128 tonnes).

Despite ever increasing pesticides use, the prevalence of food insecurity and malnourishment is not improving. Between 2019 and 2021 approximately 20 percent of people on the continent were undernourished, which has increased from 16 percent between 2016 and 2018.

There are differences in the quantities and types of pesticides used within and between the regions.

For example, while Egypt uses more fungicides than herbicides, Ethiopia uses more herbicides than fungicides. And, although Cameroon and Ghana are in the same region, Ghana uses more herbicdes (6,498 tonnes) than Cameroon (4,801 tonnes). These differences can be attributed to the type of production that characterizes the country’s agricultural model. The data provides important information about the pest problems facing farmers and therefore the ecology specific solutions that can be used in varying local contexts.

An effective management strategy for pesticides in Africa must include educational programs focusing on pesticide use, health and environmental risks, stringent policies on imports of highly hazardous pesticides (HHPs), increased government support to production systems that promote agroecology and long-term monitoring on the impacts of pesticides.

African countries are party to many conventions on the protection of human health and the environment such as Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, the Montreal Protocol and the International Code of Conduct on the Distribution and Use of Pesticides. The Inter-African Phytosanitary Council is a specialized technical office of the African Union mandated to among other things, harmonise pesticides registration on the continent. Regional institutions responsible for ensuring the safe use of pesticides also exist and include for example, the West Africa Committee for Pesticide Registration. In addition, each of the 54 African states has its own system that governs pesticide registration and use. It is worrying that despite the institutional frameworks for judicious pesticides management, most countries in Africa have not implemented an effective impact monitoring process and investments into farmer training on alternatives are lacking.

Civil society organisations advocating for the adoption of ecologically sustainable food systems and a ban on HHPs, fill a gap that governments are failing to address. Organisations such as the Pesticide Action Network-Africa which is based in Dakar, for example, are working to eliminate the harm caused by pesticides. Other organisations such as the Organic Producers and Processors Association of Zambia, Kenya Organic Agriculture Network, Egypt Biodynamic Association, and the National Federation for Organic Farming in Senegal provide training to promote IPM strategies whilst sensitizing producers, handlers, processors, consumers and policymakers on the negative effects of pesticide use on human health and the environment.