If taken as a country on its own, Lagos would be amongst the largest economies in Africa. It has been able to diversify its economy and to considerably reduce its dependence on oil allocations. But its potentials are still huge if it invested in skilled labour force, reduced its bureaucratic hurdles and adopted an inclusive development approach.

Lagos has a rich history of economic growth and transformation. Although it covers only 0.4th of Nigeria’s territorial land mass, making it the smallest state in the country, it accounts for over 60% of industrial and commercial activities in the nation. Lagos is financially viable, generating over 75% of its revenues independent of federal grants derived from oil revenues. It generates the highest internal revenue of all states in Nigeria. If taken as a country on its own, its 2010 GDP of $80 billion made it the 11th largest economy in Africa. Here, it is important to distinguish between Lagos State and its Metropolitan area. Lagos State is the area defined by the state declaration of 1967 whose boundaries had largely remained the same since the amalgamation; while the Lagos Metropolitan Area consists of the densely populated and extensively built up parts of the state, referred to as “the city” or simply “Lagos” from here on. Today, Lagos has emerged as a major hub for the headquarters of national and global companies and the complex business and professional services that support them. With a population well over 16 million, Lagos is the seventh fastest growing city in the world, and the second largest city in Africa. Lagos is not only becoming a “megacity” in terms of population but it is a global city with a substantial and growing foreign-born population and non-stop flights to hundreds of destinations around the world.

While the economy of metropolitan Lagos has enormous competitive assets, it faces challenging trends in rapid population growth, urbanisation, relentless demands for infrastructure as well as macroeconomic pressures from the national level. The city’s expansion is estimated to continue over the next couple of decades. As it is, the economic growth of Lagos – the industrial, financial and commercial nerve centre of the country – has been unable to keep pace with the geometric increase in the population size. And although the city’s internally generated revenue (IGR) is high relative to other Nigerian states, it is not sufficient to meet the increasing social welfare, infrastructural and environmental needs of the city.

Despite these challenges, Lagos has managed to generate revenue from a variety of sources, including manufacturing, transport, construction and wholesale and retail, which together account for a bulk of its GDP. The economic diversification of Lagos contrasts with the larger Nigerian economy which is heavily reliant on profits from the oil and gas industry. The oil sector accounts for 85% of Nigeria’s foreign exchange earnings, 14.85% of the nation’s GDP in the first quarter of 2014, and 4% of total employment in the country. Presently, oil prices have dropped to about $60 per barrel in comparison with $110 of June 2014, a scenario which places more pressure on the Lagos economy as citizens migrate from economically distressed states in search of employment and the central government considers new ways to capture more tax revenue from Lagos.

Concerned about the sustainability of Lagos’ economic success in the face of population and infrastructural challenges, its government in December 2014 articulated the Lagos State Development Plan (LSDP) for 2012-2025. The plan aims to transform Lagos into a model megacity that is productive, secure, sustainable, functional and safe. The main “pillars” of the vision are economic development, infrastructural development, social development, security and sustainable growth. Clearly, how the state supports the development of its manufacturing sector and engages its vast informal economy will determine whether this vision comes to light. The stars are aligned on the political horizon. In the recent general elections, the All Progressive Congress (APC) won at both the Lagos state and national levels. This political alignment has sparked fresh hope for jumpstarting economic and industrial development in Lagos. Such prospects were slim in the last decade in which the Lagos APC government worked against all political odds, constantly in battle with the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) in power at the national level.

Manufacturing in Lagos – Prospects and Challenges

Manufacturing in Lagos forms a significant part of Nigeria’s economic landscape and could, as the governor of Lagos State recently suggested, propel Nigeria into the manufacturing big leagues along with BRICs countries such as China and India. Metropolitan Lagos accounts for over 53% of manufacturing employment in Nigeria, significantly contributing to the 7% of national GDP constituted by manufacturing. In 2013 manufacturing is estimated to have contributed $35 billion to the national economy.[1] Manufacturing industries in Lagos State include food, beverages and tobacco, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, rubber and foam, cement, plastic products, basic metals and foam, steel and fabricated metal products, pulp and paper products, electrical and electronics, textile manufacturing, furniture and wood products, motor vehicles and miscellaneous assembly.

The Manufacturers Association of Nigeria (MAN), indicates that the sub-sectors dominating the manufacturing industry in Lagos are food and beverage, pharmaceutical and automobile assembly. The motor vehicle and miscellaneous industry has seen expansion in the past year with corporations such as Volkswagen of Nigeria, Nissan and the Stallion Group – producing Hyundai – setting up facilities for vehicular and motor parts assembly. More automobile factories such as Tata and Toyota are expected to set up soon. Overall, manufacturing contributes 29.6% of the GDP of the Lagos State.

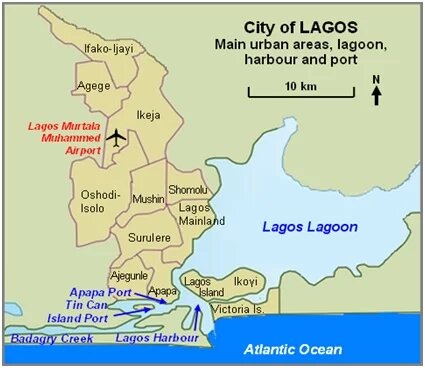

What opportunities have made industries concentrate in Lagos since the late 1970s? First, its population assures a ready labour pool for production and ready markets for consumption. Also, metropolitan Lagos features relatively superior infrastructure and is strategically located with land, air and sea connections to markets in central and western Africa region, Europe and the rest of Nigeria, easing the flow of both raw materials and processed goods.[2] The high import bill and growing population give room for more locally-produced goods. Assuming that the growing middle class increase consumption, there is room for expansion in all the sectors. Capacity utilisation for the Lagos industrial zone was about 53.85% in the 1st half of 2014, also indicating potential for growth. While these factors support local manufacturing, there are real challenges presented by human capital needs, poor regulatory enforcement, power supply deficits, aging infrastructure, multiple taxation and low industrial productivity. Lagos has a golden chance to deal decisively with these manufacturing sector challenges over the next decade so as to unlock the full potential of the city.

While prospects for economic growth through Lagos manufacturing are promising, the challenges are formidable. Take the regulatory challenge for example. Lagos manufacturers are faced with bureaucratic hurdles in the various standards and charges set by multiple regulatory agencies. Manufacturers in the sector bemoan disruptions to their operations arising from incessant inspection visits, environmental and product audits with hefty charges to manufacturers as well as long delays in product registration and certification. The burden of regulation on manufacturers needs to be eased through streamlining the requirements and interventions of state and federal regulatory agencies. Four distinct agencies regulate the food and beverages manufacturing subsector alone, with scant interagency coordination. They are the NAFDAC (National Food and Drugs Administration and Control), SON (Standards Organization of Nigeria), LASEPA (Lagos State Environmental Protection Agency), NESREA (National Environmental Standards and Regulation Agency). This regulatory maze is problematic in the light of other fundamental problems facing manufacturing in the state.

The manufacturing sector is also faced with higher production costs arising from the spike in input costs of imported raw materials following the Central Bank of Nigeria’s recent devaluation of the Naira in response to tumbling global oil prices. Manufacturing firms in Lagos, particularly those in food and beverages subsector are reeling hard from this development added on to higher energy costs and challenges of insecurity in the north that has led to a narrowing consumer base. Further the country’s inflation rate has been gradually inching higher, with implications for consumer spending power which will hurt demand for food and beverages. With weak aggregate demand, profits in the food and beverages sector declined sharply between the last quarter of 2014 and the first quarter of 2015.

Fulfilling the Promise of Lagos Manufacturing

Along with managing broader macroeconomic shocks there is scope to improve labour and capital productivity in Lagos manufacturing by investing in upgrading urban infrastructure such as transport facilities, power supply, water supply and waste management facilities. Infrastructure affects the entire process of production – from raw material supply to product distribution. Poor energy supply for example is a major infrastructural challenge that has an immense effect on production output in Lagos. Manufacturers spent an average of N57.72 million monthly to provide alternative sources of energy in the form of diesel or gas generators for production. According to the MAN economic review some manufacturers spent as much as N581.15 million in six months. At the end of 2013, manufacturers in Lagos experienced an average of 6 power outages per day with only about 3.5 hours of electricity per day.

It is crucial to note here that energy supply to homes and businesses is the responsibility of the federal government, and the State Government does not to interfere with this. The Lagos State Government, through its Energy Board agency, embarked on an energy reform strategy and has successfully commissioned five Independent Power Plants (IPPs) over the last five years. Due to power regulations, this energy generated by these IPPs can only be distributed to government agencies, public institutions such as hospitals, and street lights. National level reforms to the power sector have failed to trickle down to local industry. Infrastructural interventions and the exploration of renewable energy options would lead to improved capital productivity in environmentally sensitive ways, and the Lagos’ manufacturing sector would become an engine of inclusive growth and prosperity for the whole country.

A lot of small and medium scale industries (SMIs) operate almost totally independent of state-provided infrastructure. For instance, Samuel Toriola, a plantain flour manufacturer who inherited the business from his mother, goes to the wholesale fruit and vegetable market in Ketu to purchase plantains, which he transports to his shop – a privately-run market space in Ogudu – which is about 2km away via wheelbarrow. He dries the plantains on the zinc roof of his stall, and then grinds the dried bits into flour. On rainy days, he cannot dry his goods and is not assured a profit. In this process, Mr Toriola has used the roads, and if available at the time, power supply provided by the state. Provision of serviceable roads, adequate power supply and more mass transit links will do a lot to smooth out supply and distribution routes, and increase the efficiency of production processes. Increased efficiency will lead to an increase in profit. And this profit can be re-invested to acquire better equipment and tools – like electrical driers for the plantain manufacturer – which will lead to more efficiency and again more profit. There is also the issue of funding for manufacturing companies. The average interest rate for loans available to manufacturers from domestic banks is 23%. This is very high and is mostly unavailable to SMIs. The high cost of capital and its inaccessibility plays a large part in driving up production costs and limiting productivity.

Currently, Lagos accounts for about 10% of Nigeria’s population which is in excess of 170 million people. Although there is no lack in numbers, there is a definite shortfall with regards to skill levels, and the availability of skilled personnel is important to the expansion of manufacturing. Labour productivity in Lagos manufacturing would benefit from large-scale investment in skills training to enhance managerial roles in industry and build the productivity of machinists, maintenance engineers, welders and other industrial workers. Lagos manufacturers lag behind their global peers in production planning, supply chain management, quality, and maintenance—areas that account to their lower productivity. A recent study found that workers in Nigeria’s urban-oriented manufacturing industries actually have lower productivity than farm workers. This finding contrasts with what happens as economies develop and industrialize – productivity and incomes typically rise in tandem with workers moving out of the farm to take up work in the city.[1]

Much of the city’s largely young population would have to be trained or upskilled to provide the high level human capital required to support economic growth. The LSDP has identified a decisive plan to increase the manufacturing arm of the economy by continued support of skilled education. Human resource will be an important component of implementing this path to increase in revenue through manufacturing. Manufacturing already accounts for 30% of the state’s GDP; but the aim of the Government is to increase this to 40% over the next 10 years.

The manufacturing production value of the Lagos industrial zone was N126.01 billion in the 1st half of 2014. This figure accounts for almost half of the production value for the whole country. This visible source of revenue is somewhat handled as a “cash cow”, and as such, manufacturers in Lagos face multiple taxation. Taxes are paid to the federal as well as to local authorities. Lagos also does not offer much opportunity for physical expansion of manufacturing facilities as it is a very dense city. And even when land is acquired, new owners have to deal with “omo-niles” – people who claim to be original owners of plots of land and demand remuneration. In these ways the socio-economic environment of Lagos has been viewed as “unfriendly” for manufacturing investment and there has been a noticeable shift into other industrial zones especially to the neighbouring Ogun State zone. In the 1st half of 2014, Ogun State saw manufacturing investment of N376.57 billion which accounted for 78% of investments nationally within the same period. Lagos received N43.2 billion.

The Way Forward

However, to utilise its enormous potential, Lagos would have to find a way to make the people a part of its economic success story and to find ways to divert from the trajectory of “jobless growth”[1] which would spell social unrest in the context of its massive and mostly young population. With regards to accountability and inclusion, Lagos has a long way to go. There is no conclusive evidence to support that increased IGR has given citizens more leverage in decisions on political governance and social provision. Poverty and social exclusion is a major challenge in the broader Nigerian federation today. Poverty rates range from 16% in the South-West where Lagos is located to 50.2% in the North-East.

The LSDP tells of the government’s commitment to poverty alleviation and the government’s pledge to support SMI and informal sectors to ensure the growth of the GDP. But the pathways for dialogue between the city inhabitants, manufacturers, and the government need to be opened and expanded to sustain economic reforms and bring diverse and often excluded voices of small scale manufacturers and citizens into conversations on industrial policy and implementation. The LSDP has identified strategic governance as a major tool for the implementation of its goals. The question now is how the government will be held accountable, and what sorts of feedback mechanisms have been put in place to ensure that the development strategies are efficient. Lagos is headed by a Governor who is supported by local government heads, and an extensive network of ministries, departments, and agencies. Without a feedback system in place, there is a huge resistance in the ability of the city’s inhabitants to hold their government accountable. Looking through the LSDP, there is little regarding engaging with the people or manufacturer groups in the pursuit of economic growth in Lagos, except general government promises to listen to city stakeholders and utilise the House of Assembly to interact with the electorate on issues.

Lagos manufacturers must seize the moment to engage their government towards transforming the manufacturing sector through targeted improvements in labour and capital productivity, physical and virtual infrastructure, industrial rules and regulatory enforcement, access to credit, creating durable platforms for stakeholder engagement as well as favourable tax structures. Government must begin to develop measures that will encourage investors to remain and expand within the territory. Taxation policies need to be reviewed, more aggressive infrastructural provision schemes need to be developed, and funding should be made more accessible to industries of all scales. As Lagos is already the central commercial hub in Nigeria, such incentives will lower the cost of production and enhance its appeal to investors, allowing it to reach its full economic potential.

The combination of growing domestic demand, the concentration of resilient manufacturing industries able to tap into political support at the state and federal levels, offers Lagos product makers a once in a generation opportunity to fully emerge from the shadows of the country’s toxic dependence on the oil and gas sector.

[1] World Bank

[1] Leke, Acha; Fiorini, Reinaldo; Thompson, Fraser et. al. Nigeria’s Renewal: Delivering Inclusive Growth, McKinsey Global Institute Report, (July 2014)

[1] Leke, Acha; Fiorini, Reinaldo; Thompson, Fraser et. al. Nigeria’s Renewal: Delivering Inclusive Growth, McKinsey Global Institute Report, (July 2014)

[2] Shabi, Adebola. Manufacturing Industries and Climate Change in Lagos State. Presentation to Lagos State Environmental Protection Agency forum Victoria Island, Lagos, on 10th, April, 2012.